Is Venice 1600 years old?

The history of Venice is somehow difficult to unravel, as in its written form this was drawn up late and in a fragmentary fashion. It is interesting to notice that the archeological excavation findings do not always chronologically correspond to the written reports. In fact, the remains prove that rich hubs were already settled on various areas of the lagoon.

We have already seen how during the centuries this maritime power and commercial emporium was charged with symbolic references meant to emphasize Venice’s glory and power. This is a theme that has continued to fascinate generations of historians and researches in various fields.

ARCHEOLOGICAL FINDINGS

What happened before the year 811 AD, that is to say before the transfer of the seat of government to its present location on San Marco square, at the time called Rivoalto archipelago ?

According to some researchers and archeologists, a lot happened in what is now the lagoon but was then a soft environment made up of deltas and river estuaries connecting the Mediterranean routes to the Po Valley. Rich in resources such as fish, salt, forests, metals and amber, this area kept being used from the Imperial Age on. Such an environment ended up shaping a human society highly specialized in naval technologies and wet areas resource exploitation, men and women with the right skills to win over the environmental, cultural and commercial challenges of the High Middle Age.

Due to the little excavation scope in the lagoon, Venice still retains only a few buildings – or parts of them – that can be ascribed to the High Middle Age and that still stand above their foundations. Among them, we could count the remains of the original Saint Mark’s Chapel – provided we could also include the structures later incorporated into the church during its Contariniana phase (reconstruction beginning in 1063). Another example is represented by the Church of San Lorenzo in Castello district, in which a beautiful Bizantine style floor mosaic was found. Golden seals and coin and a VI-VII century building were also found on the Olivolo insula (part of the Rialto archipelago). During some interesting and relatively recent excavations in the garden of Ca’ Vendramin Calergi the foundations of a VI-VII century rectangular building on wooden stilts were found, complete with East Aegean anphoras and glazed ceramics.

The idea is that in the early stages of Venice the settlement was bipartite : the bishopsee at Olivo and the political center with the ducal palace at San Marco. To this we should add the innovative and interesting theory by Albert Ammerman, who after doing several core samplings in different parts of the city suggests that in VIII century there were numerous settlements along the main water way too, the Grand Canal. At that time the Olivolo with the bishopsee was playing the main institutional role because it pre exists the Ducal Palace at San Marco, as Professor Gelichi points out.

THE OLIVOLO

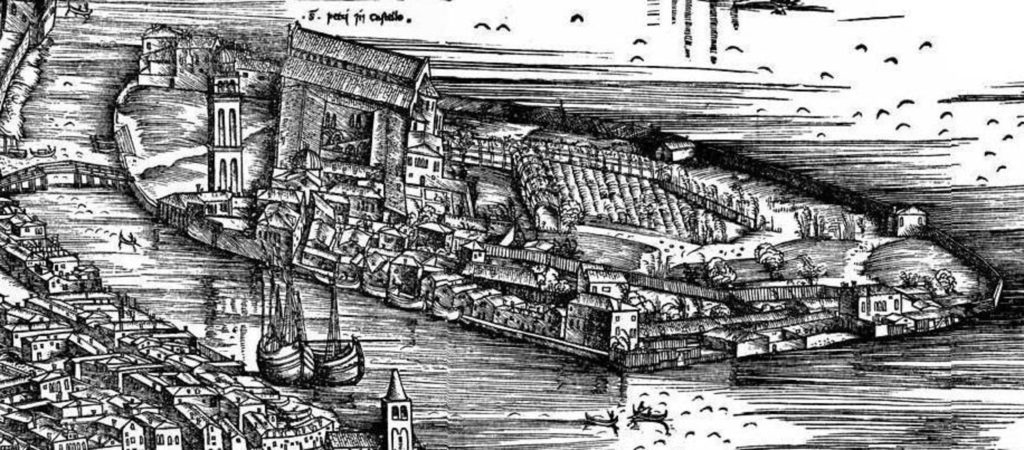

According to Gelichi, the island of Olivolo (to be found behind the Arsenale walls at the far north-east end of Venice where San Pietro in Castello’s church is now) might have been the headquarter – or one of the seats – of the Bizantine political and military Empire in the 7th century. His theory is based on the findings of architectural remains and artifacts, such as a few Byzantine golden seals.

Let’s now have a look at the toponym. The name Olivolo might result from the shape of the island.

In fact, very interestingly, he notices that in the text De Administrando Imperio written in Constantinople by the Emperor Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (composed between 948 and 952 ) Venice (named to as ‘civitas aput Rivoaltum) and Murano are called castles whereas Torcello is named ”grand emporium”. In fact “Castle” in the Byzantine sources can assume various meaning such as stronghold or wall protected settlement and scholars say that in rural areas it can mean small town. This would explain the name of the area: Olivolo of the “castle”. The name was than transmitted to the whole district of Castello, still in use today.

In the 80s on the Olivolo island excavations brought to light a wooden trunks shore-containment and a rectangular 7 mts. long building. This mid-7th century building looks very similar to some houses discovered in Torcello island and Rimini. Its foundations were made using bricks and recycled stones, and its floors were of clay. It is worth mentioning that in the area there were also found a golden tremisse belonging to emperor Eraclito. The tremisse was a coin of the late Roman empire, the weight was between 1,49 e 1,52 grams (which value corresponded to one third of the Roman solidus, that weighted 6.84 grams).

The excavations discovered also three 6th-7th century Byzantine seals (these carrying the names of important public functionaries that either lived or were sent to Olivolo on a mission.) Furthermore, this is the only area in the lagoon where the seals found during archeological diggings were three and not one or two as more commonly.

According to Gelichi, the structure pre-exististing the church of San Pietro in Castello on the Olivolo could have been an administrative building, some kind of “statio” or mansion” of the “cursus publicus”. This site must therefore have already been used for public functions during the 6th-7th centuries, before the episcopal church was built. The latter seems to have been built at the beginning of the 9th century, following the designation of the Olivolo as an episcopal seat in 775 AD.

THE DUCAL PALACE

The Historia Veneticorum by John the Deacon does not mention the exact time when Venice started as an organized settlement but states that the noble Agnello Parteciaco (or Partecipazio) transferred here the seat of the Duchy to Rivoalto from Metamauco (the previous seat of the Duchy near Lido island) in around AD 811 and with the Byzantine imperial approuval of Arsafio. Soon after 829 the remains of San Marco, the Evangelist, were secretly moved from Alexandria of Egypt, where the saint died, to Venice. During the same years the first minted currency was issued in the city ( a Ludovico the Pious Carolingian currency).

The historical-narrative sources provide very little information on the ducal palace complex: John the Deacon says it was the only building that could be defined as a palatium, we might assume it was a protected and defended structure. The palatium was clearly stone- (or brick-) built and equipped with defensive structures (e.g. towers) that would have given it prominence and protection. This protection was seemingly geared more against Venetians than against foreign enemies, as shown in the revolt against Duke Pietro IV. The palace-fortress on Rivoalto, together with the chapel which held the prized relics of San Marco, must necessarily have been of distinctive and solid features, magnificent enough to denote, in a town that would remain largely timber-built for a long time to come, the emergence of a major power.

Some scholars hypothezised the presence of Roman or Byzantine fortified buildings in the lagoon, suggesting that such a fortification would have been reused by the noble family of the Partecipazi at the transfer of the seat of the Duchy to Rivoalto, around AD 800.

THE CITY WALL

The already mentioned little excavation works possible in the city did not help confirm the real presence of a defensive wall as described by John the Deacon. According to him, at the beginning of the X century the wall extended from Castello to Santa Maria del Giglio and ended with a chain that closed the Grand Canal connecting it to the opposite shore where San Gregorio church still stands today. But we must say that there is no evidence of such a wall having existed. According to Prof.Gelichi, this seems rather a recall of the Constantinopolitan model: a work charged with a strong symbolic identity more than an efficient bulwark meant to defend the city. As already mentioned, the episcopal seat first and the ducal seat after were surely built with defensive structures.

THE FORTIFICATIONS

To defend a lagoon does not necessarily imply its fortifications. Anyone wanting to access the various inhabited islands, which constituted the irregular-shaped archipelago since at least Late Antiquity, would have had to overcome the immense problems posed by the shallow waters, the innumerable shoals and the limited landmarks.

Therefore very few fortifications have been documented in the Venetian Lagoon, at least up until the end of the 15th century. However, due to a changed political-military scenario, the Republic of Venice ended up reinforcing its boundaries with defensive structures from the end of 13th century.

This comprised the articulation of a well structured system of fortifications (towers and small castles), defending the main points of access into the lagoon’s navigable canals and inhabited islands. This system saw progressive expansion, starting from the early 16th century until the fall of the Republic in 1797. The lagoon was almost completely enclosed by a series of fortifications on artificial islets.

THE FLEET

During the course of the 9th century – as Rivoalto became the seat of power and Venice gained economic and political sway – references to the fleet and its functions become increasingly frequent in historical narrative sources.

Since then the fleet helped ensure that Venetians would become an active player on the complex chessboard of alliances. One notable example relates to the appeal made by Theodosios Baboutzikos, an ambassador of the Byzantine Emperor Theophilos, in 840 when he was on a diplomatic mission in the West to seek help for the Empire against the Arabs (Istoria Veneticorum II, 50) in the event of a disastrous war. Theodosios requested, and obtained, from Duke Pietro Tradonico, 60 warships to help with the Saracen siege of Taranto. Thus, even at this relatively early stage, Venice’s fleet was perceived as a powerful military vehicle, and one adapting to innovations emerging in the Byzantine world (Pryor and Jeffreys 2006).

Another episode in the time of the same Duke (Pietro Tradonico) recounts the construction of two large warships (in Greek, zelandriae), defined by John the Deacon as ‘bellicosas’, the likes of which had never been seen before (Istoria Veneticorum II, 55). One possibility is that the Byzantine ambassador Theodosios might have had contributed to this – perhaps he had a blueprint or had brought one such vessel with him

It is not by chance that the Venetians paid great attention to ship construction and that already in the 9th century Venice was, in the eyes of the Byzantine emperors, the prime source for requesting the assistance of a sizeable and well equipped flotilla.

CONCLUSION

According again to Prof.Gelichi, given the pre-existence of fiscal lands and public and fiscal offices in the Olivolo , the moving of the episcopal seat first and of the ducal seat after, and not far from there, might constitute a process more coherent that what it would seem.

Starting from the 10th century, Venice embarked on a journey that made her become the most important city in the Mediterranean. She embodies a certain uniqueness, defined in many different ways by historians and artists all over the world. As Frederic Lane said, Venice was a symbol of beauty, wise governance and controlled capitalism geared toward the common good. Its watery nature also contributed to invest her with a tradition of aristocratic freedom.

I would be delighted to take you through one of my historical and experiential guided tours. Visiting the original sites where all these fascinating stories took place and the most remote parts of Castello district too.

Join me and I will provide you with one of the best private guided tours of the most authentic Venetian places!

Get in touch!

Which Venice will you discover?

INTRODUCTORY TOURS

These tours are intended for first time visitors who wish to become acquainted with Venice’s main sights and landmarks, gaining an overall picture of its history and modern-day life.

IN DEPTH TOURS

Art, in all forms has been a unique ingredient of Venice’s success. Discover the magnificence of the grand Venetian architects and painters. For the ones that live in the now the contemporary art, contemporary architecture and the truly authentic glass studios where masters are at work.

UNUSUAL TOURS

These tours are intended for visitors who wish to experience areas and sites rarely seen by tourists, in both urban locations and beyond. Take this opportunity to discover truly authentic art studios, furnaces and lagoon islands with us.